As I said, in general I agree with you but your desire for deflationary economics you ignored an entire point of what I wrote: what happens when goods drop below the threshold of your monetary value?

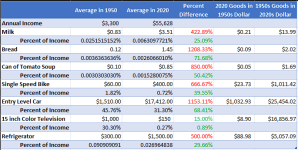

I used milk as an example because it's considered a critical foodstuff and cannot be bought by households in any other form to be reliably used and not have waste (IE, you cannot just increase the amount of milk sold per unit as a few gallons of milk is about the largest practical amount for a household to buy and store at a time). The cost of milk, as a percent of income, has DRAMATICALLY dropped in the last 70 years due to improvements in production, distribution, and preservation. How do you propose to balance for those improvements if the price drops below the minimum value of the currency (which milk was actually nearing if the US Dollar still had the same unit value as it did in 1950)?

That's why you want to keep things as stable as possible with the money supply, rather than deflationary (or excessively inflationary), because technology developments continue, improvements in distribution, production, etc. lower the costs of goods all while you have an increasing number of people needing to use the same money. A very slight inflationary money supply does not overly punish savings as the lost of value over time for the stored money is negligible from a practical standpoint or accounted for via interest paid on those savings (IE, if inflation is 1% but a savings account gives 2% interest) while also making sure that productivity and technological savings doesn't incidentally drop the the price of goods so low as to be impractical to produce and pay for.

Well, hypothetically, you could just issue ever smaller denominations. As in "a carton of milk for 50 microcents, lad". This sounds a bit strange to our lived experience, but when you consider it: is there anything all that bad about it? Would it be harmful?

If you consider it for a bit longer, though, you run into the obvious issue, which will then lead you to a built-in "braking mechanism" of sorts. The issue is: what about wages?

If you make, say, ten dollars an hour, and prices keep going down, then -- theoretically -- you can at some point buy a car for a day's wage. But obviously, in that case, all companies would go bankrupt, because they make their revenue in deflation-adjusted prices, and then have to pay comparatively

staggering sums in wages. They won't do that. So either wages are periodically adjusted (that is: lowered) to adjust for deflation... or companies periodically hike up their prices to keep revenue stable, compared to the wage costs they face.

The first option leads to the "increasingly smaller denominations" outcome. You eventually get paid, perhaps, ten cents a day, whereas a bread costs only a tiny fraction of that. (And keep in mind, each dollar and cent represents a mass in gold, so perhaps rather than creating "microcents", the money is just re-issued, and you exchange an old type dollar that's worth a certain mass in gold for ten new type dollars that are each worth a tenth of that same mass. You keep the same value either way.) There is no reason that wouldn't be workable. A factor is that people are psychologically

opposed to the lowering of their wages. So you get the inverse of the current labour relation, where the workers demand higher wages. Instead, the shoe is on the other foot, and the employers have to convince the workers to accept wages "adjusted for deflation". I think this will ultimately strengthen the position of the workers, which I intuitively feel is a good thing.

The second option would mean wages stay the same thenceforth, but companies would periodically raise their prices to adjust for the fact that deflation reduces their income. In practice, this has the same result of meaningfully limiting the effect of the deflation, and bringing actual wage-price relations far closer to a stable state. Again, this situation compares favourably to the present-day inverse situation. Now, when companies raise prices, they hide it by saying it's just because of inflation (even though in reality, they're adding a bit on the top, in Dutch this is called

graaiflatie, or "grab-flation"). In the scenario I propose, however, prices are ever decreasing, so if prices go up, everybody can instantly see that it's purely a case of the company wanting to get more. This limits what they can easily get away with. Again, this strengthens the position of the consumer, compared to how it is now.

All in all, I expect -- due to these factors -- that deflation will typically be a quite limited process, and that in practice, it's going to be closer to a stable state than one might expect. I think it'll never be static (nothing ever is), and that you will see a modest deflation-- but it won't be anything dramatic, and it'll be something that slowly happens over the centuries, not something that fucks up everybody's purchasing power in a matter of months (as we see currently).

The great benefit of what I outline here is that the balance is reached naturally. No central planning needed or wanted. The alternative of having fiduciary currency with limited inflation to keep up with economic growth in theory achieves something quite similar. And in theory, I'd certainly welcome that as an improvement! But in practice, that still requires central planing (i.e. to determine what the "right" amount of inflation should be), and that will lead to fuck-ups. Central planning always does.

So I very much prefer the kind of solution that I've outlined. I recognise that it's rather foreign to the current way of things, but I again stress that the current way is quite unnatural; and the proposed alternative is quite natural, in fact.