I don't think you understood my argument at all. In the arena of civilizations and competing moral standards, they more often than not don't care about your standards and consider them wrong, period. They are far more important for relations within a culture, or at least shared civilization.

Good or not, it sure is effective, or at least popular, we have to deal with such facts. If we try to build an ideal system on the basis of ignoring inconvenient realities, it's going to be a joke instead.

The important qualifiers here are "through Greece" and "treatment post war". The barbarians didn't care. I wonder how much of that outrage in this was due to a part of Greek civilization doing it to fellow Greeks, rather than the act itself, if it was committed by someone else, or against someone else.

Secondly, exploitative treatment post-war kinda puts a big question mark over Athen's justification for the conquest in the first place (which was supposed to be something they do reluctantly and out of strategic necessity).

Sure, and barbarians can be civilized or killed. This is why I put forward the Idea of conceptualizing the Federation as the single fully sovereign entity in existence, so that the full discussion is a within civilizational question, rather than inter. A Federation that I guess I'm theorizing currently as a Natural rights based society, though mostly because no one has really put forward an alternative system to argue morals or principles from. Because we keep not looking at principles, but just going "morality is stupid and dumb and has never existed, despite clearly existing, given the 2,500 year old moral argument referenced earlier".

Is your contention simply that being moral is stupid? That Moral people can't succeed against immoral people?. I don't understand why you keep making these arguments against civilized or moral behavior, unless you think morality and civilization are stupid.

The issue here is that with murder you have picked a very easy case for such wide universal law. After all, the treatment of such generally doesn't differ all that much across civilizations and even times. As you said, in this matter, the disagreements tend to be minor and in details.

Meanwhile, take something like free speech. Even within the EU member countries can't agree all that much on it. Nevermind EU and USA, despite being part of a shared civilization they have few pretty deep disagreements there. And let's not even get into China or the Arab world.

In terms of world consensus, the issue of homesteading\land claims is more similar to the issue of free speech (possibly even more controversial than that) than to the murder issue.

Well, the obvious conclusion is that natural law does not really imply US style, certainly as currently constructed, free speech.

Can the wolf bark at another wolf without consequence? Certainly not: the barking wolf either forces the other wolf to back down, or respond in kind, and maybe escalate. Nature is very much freedom to speak, but not freedom from consequences. Wolves don't really have freedom of speech, either within or without the wolfpack. Just prudent wolfs, who don't pick stupid fights, and imprudent wolves who do pick stupid fights and generally suffer for it.

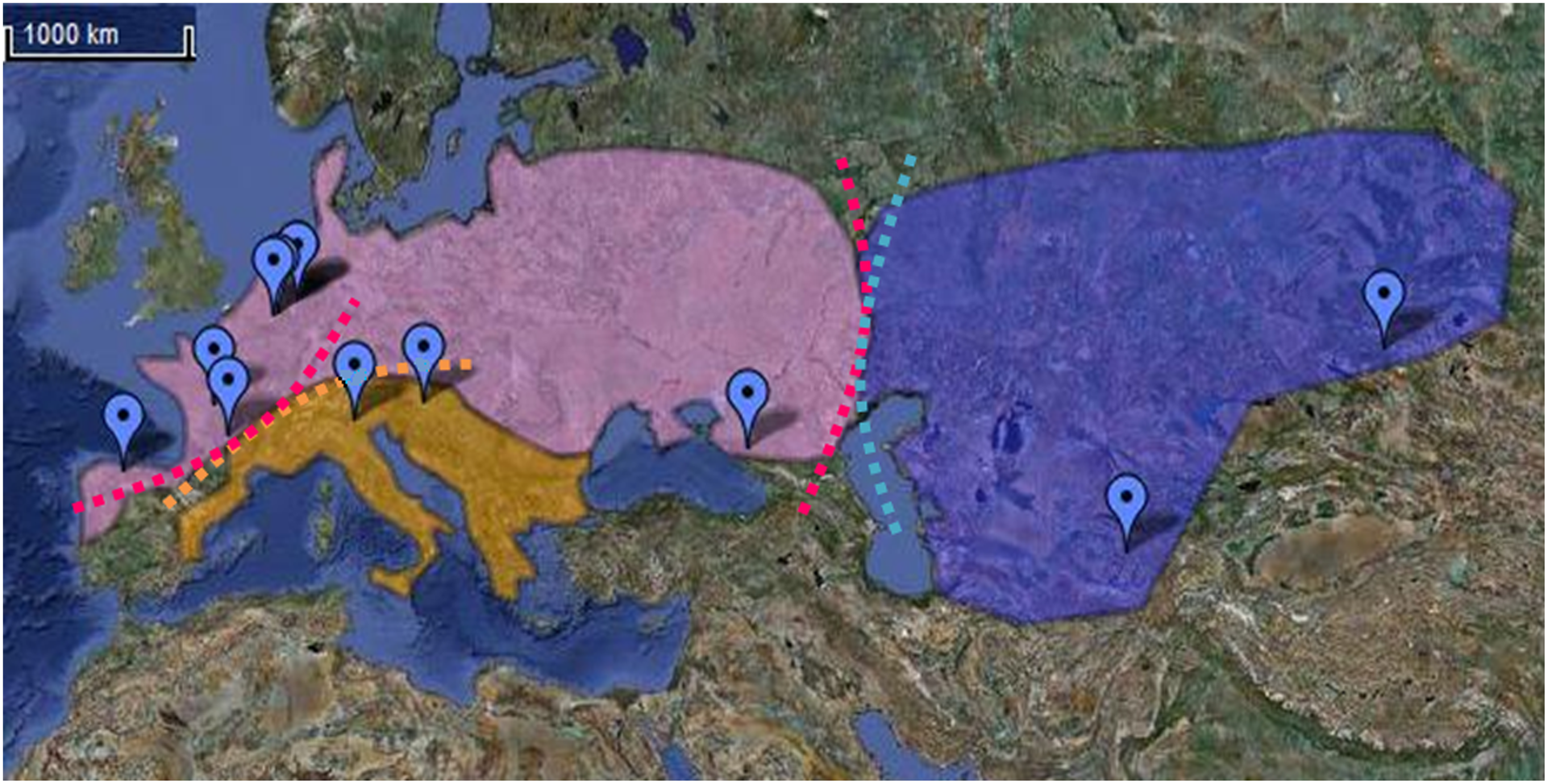

Wolves do however have very well defined territories:

Wolfpack territories

Data from the Voyageurs Wolf Project : Here is some evidence for how territorial wolves are. This map is the result of 68,000 GPS-loca...

So, looking at nature, natural law does suggest a fairly limited conception of freedom of speech, but pretty hard territorial limits.

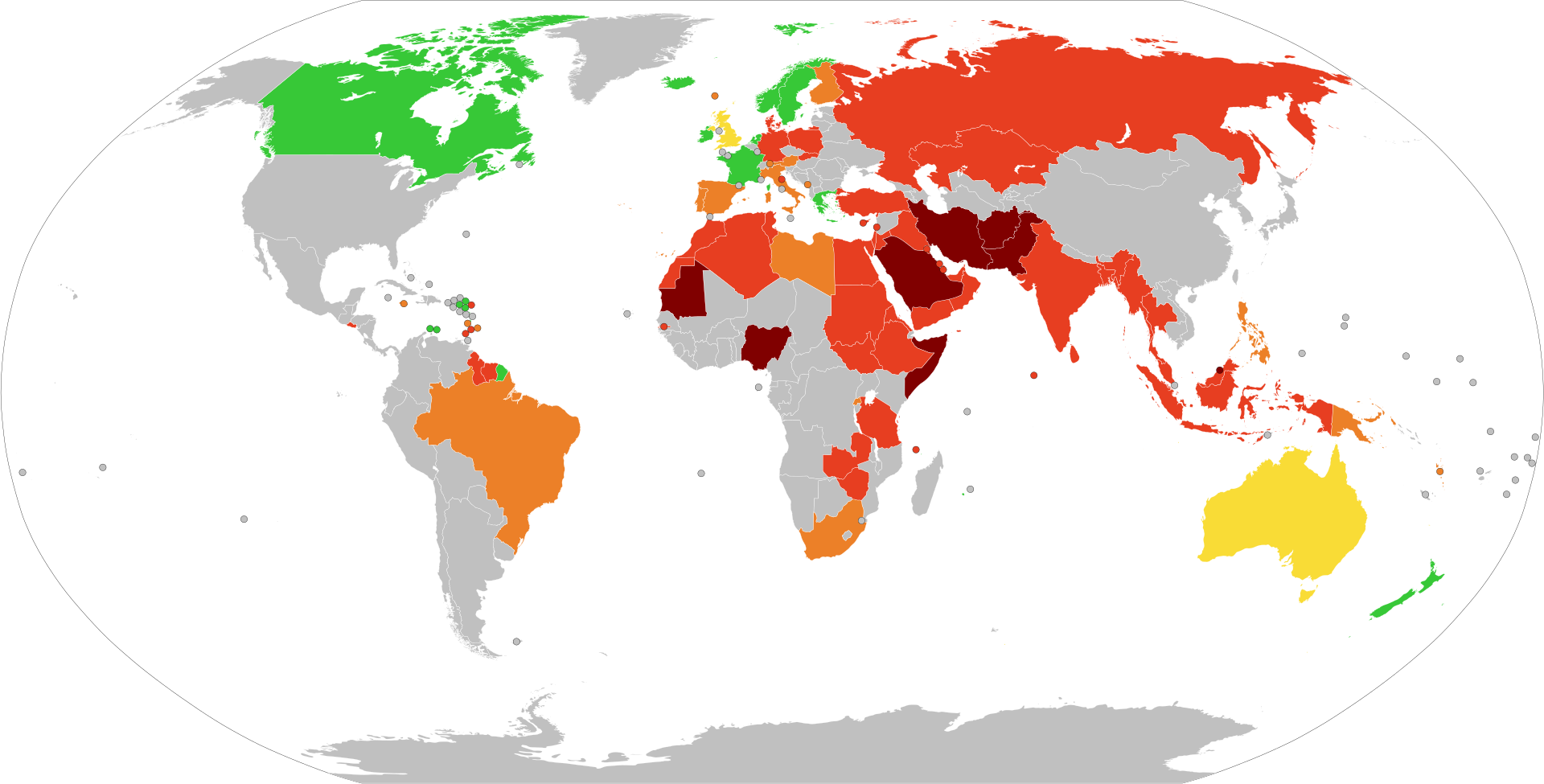

We get a similar trend looking at natural law "discovered" through tradition and human history: how many societies have allowed blasphemy against god/the gods? To find any society without such I wouldn't be shocked if you have to go all the way to, what, the 1700s? Maybe the Netherlands in the 14-15 hundreds? Even today by a global survey most of the planet has blasphemy laws of some sort, and its not more extensive only because Communist Blasphemy laws aren't called Blasphemy laws:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy_law

Even someone central to the formalization of Natural Law does not believe its doable without Religion:

Locke expands on the problems with unassisted reason and natural religion by taking the “unassisted” moral writings of philosophers like Epicurus, Seneca, Zeno, Confucius, and others as an example. During the time when they were writing, Locke explains, the law of nature was manipulated and corrupted into whatever was “convenient;” because of this lack of intellectual integrity, Locke asserts that philosophers would never be able to establish a universal concept of morality that would rally mankind together.[19] Reason, so far, is established as a faculty of judgement that is susceptible to error that Christianity helps to avoid. But if Locke says that man cannot know natural law by reason alone, then why is it that reason alone can explain Revelation? Since this question isn’t answered explicitly by Locke, we can infer that reason is missing something. On the other hand, by virtue of its noble action that seeks to understand established truth, reason is also aided by something. That something is Christianity, which according to Locke can and ought to supplement our reason in order for it to be fully formed. Reason is not a singular, homogenous, and intransigent faculty of judgement. This response, then, reveals another facet of why Christianity is reasonable: Christianity perfects our reason by working with it and enhancing it.

Locke explained in the above excerpt that Christianity aids man’s reason in the business of morality. As concerns morality, Locke establishes that whatever is “universally useful” as the standard to which men ought to “conform their manners” needs to be validated from “the authority of either reason or Revelation.”[20] If this is the case, then the effectiveness by which morality is inculcated is also a factor that Locke takes into account when considering what constitutes reasonableness. Thus, Christianity, as it is revealed in Revelation, is superior to man’s limited reason, and a man whose reason has yet to be aided by the light of Christianity would be wise to heed to the authority of Revelation for the sake of his moral formation. He wrote, “The view of Heaven and Hell, will cast a light upon the short pleasures and pains of this present state; and give attractions and encouragements to Virtue, which reason, and interest, and the Care of our selves, cannot but allow and prefer. Upon this foundation, and upon this only, Morality stands firm, and may deny all competition.”[21]

From the dichotomy that Locke drew between natural law and Revelation, and from his preference of Revelation over natural law as the better alternative because it supplies man’s reason with a necessary element or morality, we can infer a third component of Locke’s understanding of what “reasonableness” means: Christianity is useful to inculcate morality. This element is a practical point that Locke makes because he explains that Revelation helps to direct men to be more moral, which leads them to live as better citizens. In the excerpt above Locke is mentioning how morality is the “great business” of reason, but also how reason fails at this task because it alone has been insufficient to inculcate a full sense of morality. It is in this gap that religion can insert itself as that missing link between reason and morality, making it “reasonable” to use Christianity.

John Locke on "The Reasonableness of Christianity"

A primary theme that runs throughout "The Reasonableness of Christianity" is John Locke's belief that men who attempt to understand natural law and morality through their faculty of reason alone often fail at their task. But why is it that reason alone, also according to Locke, can explain...

theimaginativeconservative.org

theimaginativeconservative.org

This belief in the necessity of Religion to good morals for him went so far as to exclude athiests from his general belief in toleration.

What is of concern to society is not that we do right by God, but that we lack the intellectual understanding of why we must act within the appropriate moral boundaries (Locke does not specify what these boundaries are). This is the reasoning that will lead Locke to advocate against tolerance of non-believers.

Clearly John Locke’s religious beliefs play a major role in all of his political theory. His understanding of the social contract as an act of consent includes a basic acceptance of religious morality (the only kind of morality as far as Locke is concerned), as agreed upon by the majority. An individual, whose actions or beliefs are seen as dangerous by the majority, is perceived as breaching the contract.

As Lorenzo explains, Locke “disqualified anyone who disavowed a belief in God and an afterlife, arguing that such a disavowal ‘dissolves’ all moral ties between the individual and society” (250). Locke believes in majority rule and it is the majority which sets the requirements and expectations of society. It is also the right of the society to decide what is acceptable and what is not. As Locke expresses in his Letter on Toleration, for the sake of the community a generally tolerant attitude is advised; however exceptions exist where there is too great a risk.

As Locke says; “no opinions contrary to human society, or to those moral rules which are necessary to the preservation of civil society, are to be tolerated” (Locke, Toleration, 19). So we see that the exceptions are not limited to atheism, but to anything deemed unacceptable. I suppose Locke would liken atheism to a standard crime; we do not tolerate theft, or violence, nor would we tolerate the inciting of such behavior. Instead we advocate religion, morality and ethics, and the views of non-believers are seen as contrary to societal teachings; therefore as treacherous as the provocation of crime.

Locke does indeed target atheists specifically, in fact fervently saying; “those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of a God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist. The taking away of God, though but even in thought, dissolves all; besides also, those that by their atheism undermine and destroy all religion, can have no pretence of religion whereupon to challenge the privilege of a toleration” (Locke, Toleration, 20).

Not only does the simple idea of atheism rob you of your rights in society, but it proves you unworthy of the tolerance of others, which is apparently a benefit enjoyed by the devout exclusively. If atheists cannot be relied upon to fulfill ‘promises, covenants, and oaths,’ then they cannot be relied upon to be loyal to the ultimate contract which binds each man to all other members of society, government, and the laws thus established.

John Locke on Equality, Toleration, and the Atheist Exception

Political philosopher and social psychologist, John Locke was an outspoken supporter of equal rights within a governed society. He espoused the natural rights of man, namely the right to life, liberty and property, and he articulated that every government...

So, by classic Natural rights, I'm not sure there actually is a "right" to freedom of speech. Merely prudent or imprudent management of speech. The John Locke diagnosis on our speech problems would likely not be over any particular details of the management of it, but that its being imprudently managed by athiests and satanists, when speech really should be managed by good Christians, via burning reddit Athiests on stakes. That would solve the speech problem the traditional way.

A child does not have a right to say anything he wants to his father. A good father however will be prudent in his responses to what his child says, and know when to ignore the child, talk to the child, chide the child, or whip the child. So too is my impression of free speech in Natural Law.

Property rights, meanwhile, do seem to exist in Natural law. So, more complicated than Murder in natural law, but actually exists, unlike freedom of speech.

I did signal earlier with the "do companies really need to own land?" question that I'm prepared for Natural Law to lead somewhere else besides modern US norms.

Take the principle one - the qualifier "unjust" can get pretty wild. Sure, this works well enough if you have a space EU or space USA. Might even work with space West.

But say, Pakistan joins the space EU, and now you may have a problem. As it happens, someone in Balochistan gets killed for blasphemy. Was it murder? By the principles of space EU, yes, it was murder, and not even some boring one, but a particularly aggravated kind, might even be considered especially severely as a hate crime and act of terror. Meanwhile, in Pakistan that's gonna be controversy at best, with many arguing that killing a blasphemer not only isn't murder, because it's not unjust, but in fact it's even the righteous thing to do, and letting the blasphemer live would be an injustice if anything.

Or in a historical case relevant to our discussion of inter-civilizational ethics, the famous Charles Napier quote about handling the burning of widows.

Heh, I just got to this part after writing the rest of the above, so thinking through the logic of natural law, the Pakistani situation might be more in line with natural law, and the west might be dangerously permissive.

Or natural law says its a local question of prudent governance. Its not like we don't have our own blasphemy, we just don't punish it in same way (Germany I think just fines you).

Though were also getting into something a bit different than murder though, if this is the even being discussed.

This enraged Laasi who went to the Hub city police station to lodge a complaint of blasphemy against Kumar though he was the first to blaspheme Kumar’s beliefs. Laasi was accompanied by local leaders of the Jamiat Ulema-i-Pakistan, who adhere to the Barelvi sect.

When the police looked into the WhatsApp communications, the screen shots that Laasi provided to the police to get Kumar arrested showed he was the first to hurl abuse at Kumar’s religion. The Station House Officer of Hub city police station, Ataullah Nomani, told Laasi that he started all this by abusing the religious beliefs of the Baloch Hindu man so he detained him as well. To his rude awakening Laasi was informed by the police officer that blaspheming of any religion, not just Islam, is against the law.

It may in fact be prudent government policy to arrest troublemakers, especially when the situation is so high strung as seems to be the case there. I'm open to the argument. The spiraling into mob violence afterwards less a sign of good governance.