Doomsought

Well-known member

Good for them, it well definitely help their trade relations.Worth noting Puerto Rico has the same rate of English usage as Mexico, and the latter is even IOTL moving towards a bilingual education system.

Good for them, it well definitely help their trade relations.Worth noting Puerto Rico has the same rate of English usage as Mexico, and the latter is even IOTL moving towards a bilingual education system.

There is no way the Republican Party would support this, given it would shift the US to Dem one party rule.

Strange as it seems to us now, during the early phases of the "Unipolar Moment" and enduring for at least the entirety of the 1990s, there actually was some very strong indications to suggest Mexico could plausibly be added to the United States. Noel Maurer had this to say some years ago:

Noel worked for the U.S. Federal Government for about two years in Mexico and is an Associate Professor at GWU, so he does have some credentials to be speaking on this. As for the Este País poll, here is a citation of it. Just shy of a decade later they asked the same question again and found the support had endured. Outside of the 59% supporting it on the pre-condition of improved living standards, 21% supported doing such without any pre-conditions.

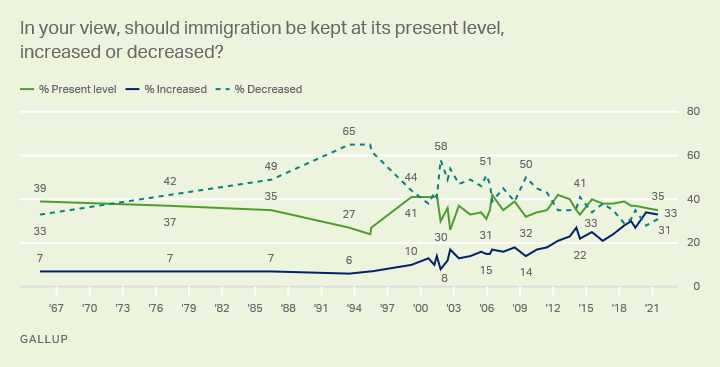

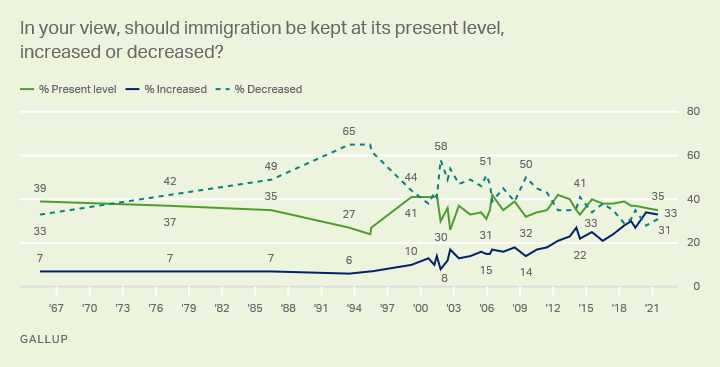

Americans were relatively hostile towards immigration in the 1990s, and you expect them to be OK with the absorption of 100+ million Mexicans? :Up to this point I've mainly been focused in on the North American side of things, so I wanted to take a second to consider the wider ranging ramifications while also tying it into my current research about the late Cold War. An obvious question about a scenario in the 1980s-1990s is the impact on the USSR and the East Bloc. To answer that, we must first understand what exactly happened in the first place. To answer that, I quote from Gorbachev vs. Deng: A Review of Chris Miller’s The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy:

As oil prices fell, Gorbachev tried to maintain living standards which resulted in major growth in the budget deficit. Before Gorbachev came to power, the budget was balanced or even had a small surplus. In 1985, the deficit grew to 2% GDP, by 1990, it reached 10% GDP. In 1991, the last year of the Soviet Union, the deficit exceeded astronomical 30% GDP (p. 152).The fiscal crisis was partly explained by a collapse in global oil prices but was partly handmade. First, Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign reduced revenues from excise taxes. Second, in order to keep the industrial and agricultural lobbies happy, the government continued to subsidize their inputs and raise prices for their outputs. At the same time, in order to pacify the general public, consumer prices were kept low. Gorbachev also avoided cutting expenditure on public goods and tried to maintain living standards. He decided that–unlike Deng–he would not use force to suppress protesters and therefore tried to avoid the situation where people took to the street to voice their economic grievances.To fund the deficit, the government resorted to borrowing. The foreign debt increased from 30% of GDP in 1985 to 80% of GDP in 1991 (p. 152). As the markets were growing increasingly reluctant to lend, the government funded the deficit by printing money. The official prices were still controlled, so the monetization of budget deficit resulted in “repressed inflation”, increased shortages and higher prices in black markets. Eventually the Soviet Union ran out of cash and collapsed. Miller’s account shows that both oil price shock and the impact of the anti-alcohol campaign were not the major drivers of the fiscal crisis. The main factors were lack of resolve in tackling the interest groups and in maintaining fiscal discipline as well as incompetence in basic economics.

So, obviously the collapse in oil prices being much deeper from 1985 onwards would be disastrous, but it doesn't need to be fatal for the Soviets. Without the ability to stabilize living standards and/or buy off interest groups, it's likely Gorbachev will have a short tenure as General Secretary, perhaps being ousted by 1987 or 1988. The key difference between this ATL effort and the OTL 1991 coup will be that Gorby will not have yet destroyed the CPSU as an entity nor is there been years for Glasnost to take root. Most likely Gorbachev would be replaced by Ligachev or maybe Ryzhkov, who are still economically reformist but differ in the ways and hows; Ryzhkov, for example, was against the Anti-Alcohol campaign because of its impact on excise taxes. We will go with Ligachev, however, for the sake of the argument.

With the authority of the CPSU still in effect, the new General Secretary will be able to use force to suppress dissent like Deng did in China while using the organs of the party to hold the nation together while reforms are conducted. Anti-Gorbachev putsch could open the way for renewed Anti-Corruption purges as occurred under Andropov, which in of itself would boost economic growth by removing deadweight so to speak, while also allowing Ligachev to combat the interest groups in a way Gorbachev was never able to/tried to. Likewise, the removal of Mexico from oil markets for a time from 1988 on will help alleviate some of the stress, as would the ability to cut defense spending because of the shifting U.S. focus from Europe to the Homeland to deal with the Mexican situation. Thus, it's entirely possible this would result in the USSR economically reforming successfully and surviving.

I feel like it is too late, however, to save the East Bloc as a whole although Ligachev can manage to extend things out; instead of it all collapsing from 1987-1989, perhaps it's a more drawn out process extending from 1990 to 1995. The loss of the East Bloc would probably sufficiently tarnish the CPSU that real political reforms following this event would have to come, which would probably require something like the New Union Treaty with several of the SSRs (Baltics, Caucasus and Ukraine) breaking off. Still, a core USSR of the RSFSR, Central Asia and Belarus could be retained.

Americans were relatively hostile towards immigration in the 1990s, and you expect them to be OK with the absorption of 100+ million Mexicans? :

As for the Soviet Union, Russian leader Boris Yeltsin had absolutely no interest in a union without Ukraine, which is ironic considering that his successor Vladimir Putin currently has a Eurasian Economic Union without Ukraine, though not for a lack of trying!

It takes two to tango. While Mexicans might have been interested in this, I doubt that Americans would have been. For one, the US would have likely needed to subsidize Mexico for a very long time, possibly indefinitely. Secondly, the demographic effect could be perceived as being a big deal by many Americans. You need to keep in mind that even in 2006-2007 and 2013, amnesty for undocumented immigrants was defeated due to efforts by the Republican Party base. Here, we're talking about an absorption of 10+ times that many Latin Americans. If anything, I suspect that any such attempt might very well trigger a huge upsurge of white nationalism in the US earlier. It wouldn't necessarily always be phrased in racial terms, of course, but I could certainly see a lot of conservative Americans saying something along the lines of "Well, if Mexico is a dysfunctional country, and we're going to annex them, how exactly do we know that they're not going to bring their dysfunction over here?" or something like that.

The US previously absorbed Puerto Rico and the Danish West Indies (US Virgin Islands), but those involved much smaller populations. Ditto for the Mexican Cession.

A US union with Canada could be more popular among Americans since Canada has a comparable quality of life to the US and also comparable demographics. Still, I wonder if conservative Americans might oppose even this since Canadians are notable for their liberalism--except to some extent on immigration policy.

Worth noting Reagan got through an amnesty in 1986 without noticeable political blowback. Undoubtedly the U.S. public is broadly Anti-Immigration in general, especially the illegal variety, but even in present times there tends to be a mollified attitude towards legal immigration and directly annexing-and thus not only legal but citizens-certainly qualifies. It's worth noting both parties since 2016 have directly in their campaign platforms calls to admit Puerto Rico in as a state.

Yeltsin here is either a good member of the CCCP not raising issues in this regard or he has been removed.

I think a lot of the modern or near recent exploits on immigration have to be considered in the vein of the times. For example, see Nixon:

The United States of America is witnessing a growing Latin American voting demographic, and many might be surprised to learn that the first “Latino” President was, in fact, Richard Nixon. In 1969, his first year in office, he established the Cabinet Committee on Opportunities for Spanish Speaking People.Throughout his Presidency, he appointed more Latinos than any preceding President, including John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. He remained unsurpassed in those numbers until Bill Clinton’s Presidency in the 1990’s.Over four decades ago, Hispanics in the United States found themselves exercising more power in a Presidential campaign that at any other time in American history.Seeking re-election, President Nixon reached out to the Latino community by discussing his strategy for funding education, health, small businesses and other programs in Latin American communities in areas like Texas, California, and in the Southwest. Some called it the Nixon Hispanic Strategy.Nixon received 40 percent of the Latino vote, by most estimates, in the 1972 re-election.Nixon was often joined in his campaign by some of his most prominent Latino appointees, including Cabinet Committee Chairman Henry Ramirez, U.S. Treasurer Ramona Banuelos, and Office of the Economic Opportunity head Phillip Sanchez.Even today, after recent Presidents such as Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama made a substantial effort to appeal to Latin American communities, Presidents Nixon’s historic appointments still warrants a singular recognition.

Reagan supported amnesty in 1986 but this didn't help the GOP afterwards, which might have caused the GOP base to learn the lesson that the GOP is unlikely to get more than 40% of the Hispanic vote even in a very good year.

As for Puerto Rico, you're talking about three million Puerto Ricans, which is a very far cry from 100+ million Mexicans.

The polling that I showed you appears to pertain to immigration in general rather than exclusively to the illegal variety. But if you're curious, the GOP might have become more hostile to large-scale legal immigration as well over the last several years, in part due to political concerns (immigrants and their descendants voting for the Left) and in part due to their base's fears of the "Great Replacement".

AFAIK, Gorbachev didn't want a union without Ukraine either.

I think that requires both a high degree of foresight and an estimation of what the relevant political factions are at the time. The element of the GOP base that you cite, which stopped Bush's efforts in 2006-2007, was not able to do so with Reagan in 1986; this suggests to me it had yet to congeal politically or was yet to be influential enough. Certainly, that Bush felt he could try this again in the late 2000s suggests it was an open question to leaders then, and the fact Reagan is lionized to this day by a large segment of the GOP suggests they've not begrudged him for that. Certainly, they didn't reject Bush in 1988 in reaction either.

Understandably true, but Mexican Americans even back in the early 1990s were a much larger and politically powerful voting bloc than Puerto Ricans are and are ever likely to be. MAs have been a keen factor in California going to the Democrats, and are politically powerful in Texas, Arizona and New Mexico. That's eight senators and two of the three largest States by population, not counting the business community given the position of Mexico in U.S. trade in 1990.

This I see as possible, or even that the Democrats might become the party hostile to immigration; regardless, a large scale reduction in such post annexation could definitely happen and I don't see that as an issue personally.

I thought your argument was a Union with Ukraine would be rejected?

Yes, it would be, by either Gorbachev or Yeltsin, depending on whose opinion here is actually relevant. And if Gorby gets overthrown by hardliners, then they will certainly use force to keep Ukraine in the Union.

Again, I'm confused by your argument; Gorby wanted to keep Ukraine in the Union and Yeltsin historically favored breaking up the Union. These are different positions?

AFAIK, Yeltsin only favored breaking up the Union after it became clear that Ukraine was not going to participate in any (new) Union. Had Ukraine been willing to participate, so would Yeltsin.

My basic assumption here is that Yeltsin is a non-factor; he was on the verge of being sidelined in 1988 and it's really only luck he in position to assert the influence he historically did.

OK, but even so, you need either a Soviet or a Russian leader who would actually be willing to have a (new) Union without Ukraine in order for the Soviet Union to survive.

Gorbachev wanted Ukraine in the Union, but I doubt he would use force to do so; the Union would continue on without it.

No, the issue was that without Ukraine, the Slavic percentage in the Soviet Union would become too small and diluted. You'd see a union that was only 60% or so Slavic, which is too close for comfort for Russian nationalists.