raharris1973

Well-known member

This is not an uncommon scenario, but what if the US does not join into WWI, especially in 1917?

To make things clear, I’ll specify exactly what changes from our actual history to make it not happen.

World events in Europe, World War I and its various fronts, North America including the USA and Mexico, and every place else run almost precisely as they did in real history up through 1916, including Wilson’s reelection in November that year.

The slight divergence from our timeline that starts happening in 1916 is an elevated level of petty personal political drama in the military circles around the Kaiser, that turns out to have consequences that are not so petty, but are policy relevant, after all.

They start in the mind of Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Alexander_von_Müller) Chief of the German Imperial Naval Cabinet and personal friend of the Kaiser, and distress he feels over the increased tension in early 1916 that led to the resignation of Alfred Von Tirpitz as State Secretary of the Imperial Naval Office on March 15, 1916. The famous Tirpitz, aligned with the Kaiser for years as a booster of the large fleet, had increasingly been at odds with the Kaiser and Bethman-Hollweg over restrictions on U-Boat rules of engagement in the aftermath of the Lusitania sinking and the American negative reaction to it. Tirpitz agitated against restrictions in the press, and threatened to resign multiple times before doing so, causing the Kaiser stress, and thus causing Muller stress.

In this timeline, his protectiveness of the Kaiser, and his anger at Tirpitz prima donna self-aggrandizing style, angers Muller a great deal and makes him warier of prima donna Admirals and Generals trying to push around the Kaiser.

Admiral like OTL takes care of personal naval/military management and briefing of the Kaiser, along with his Army counterpart Generaloberst Moriz Von Lyncker, and they see it as their duty to keep the Kaiser’s spirits up, keep him engaged in affairs of state and public appearances, but well-advised in his and the state’s best interest, which both Muller and Von Lyncker see as the same thing.’’

But the Tirpitz drama turns both men off to out-of-control, prima donna flag officers, and encourages them, especially Muller, to cultivate their own information and support networks in their services.

In Muller’s case, this means over 1916 learning more about the U-Boat service and its operations. U-Boat production. Tactics. Talks with skippers. One of the first things he learns by spring or summer 1916 is how, despite how enthusiastic Tirpitz was unrestricted submarine warfare by 1915 and 1916, he did very little pre-war, or even up until the day he resigned, to build very many of them for a mass unrestricted campaign, compared to other ship types. This increases Muller’s distaste for the man.

Over the rest of the year he learns other things, from engagements with U-Boat Captains/skippers. The difference between following Cruiser rules and unrestricted rules actually is not that urgent to them, and most of the time, for the armament they have cruiser tactics are what they naturally use, because they are better armed and can more effectively see what they are doing against targets when they surface and use their guns rather than their sparse number of torpedoes. It’s also good for crew exercise and morale when they get to surface and storm aboard a captured prize. This is contrary to Muller’s expectation, when it turns out that it is more the Admirals, not Captains and crew, who chafe at the ROE restrictions.

This further adds to Muller’s skepticism of the unrestricted submarine chorus, now being championed by Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, head of the Imperial Admiralty Staff, and the popular Generals of OberOst, Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

Muller makes contact with naval intelligence people, who on the one hand are supporting “analysis” naval figures like Holtzendorff are using to purport that unrestricted ROE would be a huge factor in crippling British tonnage for vital imports, but also obtains reports and data on German interned merchant tonnage in US ports, US fleet strength including in destroyers, and the role of US and other third party and western hemisphere ports in any successful blockade breaking Germany is accomplishing. Much or all of this material being left on the cutting room floor when being ultimately prepared for and presented by Holtzendorff.

Ultimately, Muller’s efforts, pre-briefing of the Kaiser at opportune moments and making allies in the navy and sowing doubts alters the bureaucratic battle within the German fleet and military that led to the presentation of unrestricted submarine warfare as a “miracle cure” for Germany’s desperate war effort by the end of 1916.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

While it would be dramatically fun to have Muller present a counter-memo to Holtzendorff debunking his memo, Pless conference - Wikipedia

Muller probably would have had to do groundwork beforehand to undermine it, pointing to its blindspots or errors which included:

…but they don’t rule it out either.

In a compromise, they keep up the current “sharpened” U-Boat campaign against Allied merchant vessels, virtually all armed at this point. They also commit to shift naval construction allocations to enhance numbers of submarines and their torpedo capabilities of submarine for unwarned sinkings for that option and under waterline damage.

With a greater focus in mind on the naval, and not just military, implications of the USA entering the war against Germany in reaction to an unrestricted U-Boat campaign, the idea that in our timeline led to the Zimmerman Telegram, an offer of alliance to Mexico, and then through Mexico, to Japan, is pursued. But, the whole matter is handled with greater care and security. No messages are sent to Zimmerman over wireless or the wires, even encrypted. Instead, only encrypted *written* instructions delivered in another voyage of the cargo submarine Deutschland, set for January-February 1917 to America and to be courier conveyed to Carranza, with the overture to Japan discussed in Mexico City, in their embassy if possible.

The intention is to line up the contingent alliances with Mexico and Japan *before* authorizing unrestricted submarine warfare, and not authorizing it beforehand. And the hardcopy/in-person delivery method makes sure Britain’s Room 40 never sees any of the discussion, which almost certainly dead-ends without conclusion. From Muller and like-minded people’s point of view, Japan with its Navy is the more important of the two, to offset a possible entry of the US Navy, However, Japan switching sides is ultimately even more outlandish than Mexican-American war. Without signals intercepts, the British and Americans hear nothing of the German overtures to Mexico or Japan, except the vaguest rumors, or whatever those two countries choose to share. The Mexicans would say nothing and keep mum I’d say. And while the Japan would report an offer, at the same time, playing loyal while highlighting their value and options, it might not just be regarded in British circles as Japanese self-aggrandizement for diplomatic leverage.

OK – so Germany is going into January, February, March, 1917 operating its ground and naval forces consistently. No new crisis with the USA, and bam! we have the February Revolution in Russia overthrowing the Tsar.

In April 1917 we have the Nivelle Offensive and then mutinies by French troops.

I will go ahead and make another interpretive leap. The Entente will figure out how to survive 1917 financially and economically.

There are some thoughts they could not, and they were running out of backing collateral in North America for loans. And indeed, the Wilson Administration was advising lenders not to make unsecured loans to overseas borrowers.

Certainly, without declaring war, which is not happening, the US government is not guaranteeing Entente loans or granting unlimited credit. Nor can present a “Liberty Loan” as a patriotic duty or sell war bonds for US defense or Entente purposes. And there were internal British memos about running out of financial liquidity at some point in spring 1917.

However, these British memos were likely based on maintaining certain fiscal and trade orthodoxies and assumed non-imposition of different types of austerity and rationing that Britain’s coalition government would have been willing to do rather than lose the war, even if the measures would have been anathema to an Asquithian Liberal government following its 1914 and beforehand principles.

Additionally, while American creditors could in theory start calling British and other Entente loans short, and strictly to account, and then seizing British-owned collateral for non-payment, causing a run on that, resulting in its liquidation and a drying up of credit, that may not be the most likely thing to happen. Banking and industrial concerns were not as strictly separated then, and big lenders would know abruptly pulling credit, rather than extending and stretching out repayment terms, could kill export markets expected for the quarters ahead instantly. So some concerns with cross-ownership across different sectors may literally continue to bank on British and Entente victory, having sunk so much business and investment in them already, convinced they will win, and counting on them as product markets in the near-term.

In any case, the British do still have their shipping resources, untapped, as-yet-untaxed resources and even if running into difficulty getting credit for purchases in the US, can still make vast food and raw material purchases and some light manufacturing purchases from their Dominions and to some extent Latin America.

Now British and Allied shipping should still face a hard time from the German U-Boat campaign, even as it remains under restrictions. It should get worse from them through June-July-August, even if never as bad as it got in real history. And I would expect the British would start convoying by the time they need to, when they calculate that is the more efficient and sustainable overall alternative.

In any case, in real history, and in this timeline, Germany and Austria and the Ottomans were *utterly unable* to go over onto the offensive on *land* against the western powers at any point between August 1916 and March 1918 (a whole 20 months!) or against Italy between August 1916 and October 1917 (14 months) and I don’t see what would make that change here. From August-December 1916, all the Central Powers could accomplish on land in Europe was holding off the Brusilov offensive, mounting a counterattack to it, and counterattacking the Romanians and squeezing them out of Wallachia and Bucharest. Any other successes by the Bulgarians and Ottomans were defensive stalling, and in Anatolia/Caucus, the Turks were failing at that.

In 1917, the Central Powers, despite the rot and end of discipline and motivation in the Central Powers and the mutinies against senseless offensives in France, were unable to mount any land offensives from January through August of the that year. And they had to fend of persistent British assaults in Flanders from May or June through November, the brief French Nivelle offensive in April, some Italian offensives in the summer, a feeble sally from Salonika that year, a successful British advance in Mesopotamia, and British gains in southern Palestine and Jerusalem by the end of the year along with Arab Revolt actions.

And this was all in our timeline before US troops were really in the trenches in any quantity. So the absence of US forces from the war and the trenches through August 1917 does not look at all like it provides Germany or the Central Powers a war-winning opportunity in that time.

What Germany was able to do in 1917 was mount a defense and counter-attack that manhandled Russia’s June Kerensky offensive, and sent Russian morale further plummeting.

Then, in September, taking advantage on ongoing rot/melt of Russian forces, the Germans took Riga.

Then in October-November, the Germans and Austrians together battered the Italians at Caporetto and threw them out of much of Venezia back to the Piave.

Without America in the war, there’s not an apparent opportunity for the Germans to advance to an enemy capital in 1917 to claim a victory, but things can’t be better for the Allies either. The Allies’ offensives are failing.

It is a legitimate question if the Russian Provisional Government even *attempts* an offensive. In our timeline, the Provisional Government was being prodded forward and pep-talked into not only keeping in the fight, but attacking by the mission of American Elihu-Root, who made clear that American financial largesse was on offer for Russia *if* it fought for victory, but “no fight, no loan”. Without the Yankee carrot, the British and French alone might not have enough to offer the Russians to motivate a real offensive from them, even if the Russians would not yet be ready to make a separate peace. Indeed, if Wilson is still on the outside, not wanting a German victory, but not wanting *anybody’s* victory, and supporting a negotiated peace, Wilson might be finding the Russian democratic socialist parties, with their presence in the Petrograd Soviet and in some Provisional Government posts, with their talk of” no annexations and no indemnities” among the most receptive among any politicians in any belligerent state.

*Without* the US having declared war on the Central Powers, and that being noted as a growing danger for them, it is an open question whether or not the Center and Social Democratic parties in the Reichstag voice support for a negotiated peace in July 1917 as they did in our timeline. It is also an open question whether Pope Benedict is moved to offer is August 1917 mediation proposal, which some have interpreted as motivated by the danger to the Catholic Habsburg monarchy by this point in time.

I imagine Britain’s blockade would continue to tighten around Germany, although be little less airtight, a little more leaky, with the USA not a belligerent. It would still get harsher.

But unless things change to somehow produce a negotiated end to the war by November 1917 – not absolutely impossible, but still requiring a near-miracle, and highly unlikely, we would likely have a Bolshevik Soviet revolution pulling Russia out of the war by this point in time.

That would probably ease pressure in Germany for unrestricted submarine warfare, though it still wouldn’t be ruled out, and even though the blockade would be stinging.

The persistent effects of blockade, even without American participation in the war and prospect of ever-growing numbers of American troops, probably would *still motivate* Germany to invest in a spring 1918 do-or-die offensive in the west.

This would have to follow a punishment expedition in the east to stop dilly-dallying and get the Bolsheviks to sign the Brest-Litovsk peace.

By March 1918, we do have some questions about how the Allies have postured themselves defensively, not having American troops in France or on the way.

Have the French raised significantly greater numbers of colonial troops from North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indochina, trained them, armed them, and put threm in the battle-lines in France or at least in the fields and factories of France in numbers far exceeding our timeline?

Have the British sent significantly more of their own men, Dominion men, and possibly men from non-white colonies like India, the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa to fronts in the Middle East, Salonika, and France?

Is that helping keep manpower in terms of battalions comparable to our timeline or not?

If not, why not?

Have the British or French in any manner found something sufficient to bribe Japan with to send a Japanese Expeditionary Force (JEF) to Europe to fight with them? Has it even been discussed? Has Japan mentioned a price? Did the Allies turn away horrified at the price or think about it? –Ultimately, I think any such bargain is really unlikely.

Given the technology of the time, and the tactics, I don’t think a decisive breakthrough and exploitation of Allied lines, gaining either the Channel ports, or Paris, is likely in 1918, and failure to meet these objectives will be devastating to German morale.

However, there is an important question remaining.

Would the British and French need to pull back and abandon peripheral fronts, or starve them, to survive the 1918 German offensive?

For example, pull out of Salonika, dismount the troops in Marseilles or the Channel ports, and head to the lines. Pull back any troops sent to Italy after Caporetto. Strip the forces in the Mideast fronts, Palestine and Mesopotamia, to the bare minimum, and get them back to France?

[Also, would none of the British, French, nor Italians have any troops to spare to intervene in Russia to guard supplies or help the White Russians? I would not see the Americans involved in Russia, even in Siberia, if they are not already in WWI. This leaves only the Japanese to possibly involve themselves.]

If the Allies have to do this to survive, they stop the Germans, but they are too exhausted to immediately launch non-stop counter-attacks beating the Germans back. The Allies have to cut off the most threatening forward positions, build up colonial reinforcements and supplies, build up gas and tanks and aircraft, keep up the blockade, and be ready to have a go in 1919.

And thanks to withdrawals in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Italy, the Central Powers of the Ottomans, Bulgarians, and Austro-Hungarians will be under less pressure along with Germany and they’ll all make it through another nasty winter and New Year.

However – If on the other hand, the Allies are able to halt the Germans in the west through external/colonial/home reinforcements, German logistical over-reach, while *not* stripping down the other fronts, it is a different story.

The Allies without the Americans would probably have too thin a manpower buffer to prosecute the OTL 100 days offensive of hammer blows in the west. But the men in the west who survived the German onslaught and building up for 1919 will be cheered a bit by good battle news in the fall in September from the Middle East, and then the Balkans from Vardar Macedonia, as in October and November the Bulgarians, then Ottomans, and then Austro-Hungarians collapse.

To the surprise of almost all, the decisive campaigns entering German soil over the winter months of 1918-1919, and compelling German surrender and setting off German revolution are not on the western front, they are rather the efforts led by Armando Diaz crossing Austrian Tyrol, Austria proper, Vienna, and Salzburg, to advance to Munich, and parallel advances by Franchet D’Esperey’s L’Armee D’Orient of Frenchmen, Serbs, and Greeks, riding the Austro-Hungarian rails, soon joined by Czech and Polish volunteers, collecting in Prague, advancing into Saxony and Silesia, and then on to Berlin and Brandenburg from the south. The role of the hard-worked western front armies is to keep contact with and pressure on the German western front forces and collect increasing numbers of PoWs.

In Germany’s increasingly desperate situation, there are attempts to shift forces to close the wide open breach in the south and east at the tail end of the war, by transferring troops and units from the western front via the rails to Bavaria, Saxony, Brandenburg. However, success is limited. Because of the late start, Allied forces are reported breaching the Reich borders at Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, before much in the way of any transfers have been completed. Some local commanders who haven’t lost faith resist redeployments, not wanting their sectors in the west to break. Other units embarked on the rails and roads, “get lost” on their way to the other fronts as soldiers desert and wander home to check on family rather than stay in order or mass on the other border. Some troops resort to minor self-wounding, self-maiming to avoid further duty. Others in more exposed positions, especially as bad news from the southeast spreads, surrender to the nearest Allied forces to get rations and a dry cot.

These forces all add up to total disintegration of the German position before the winter is over, possibly before the end of February, definitely before the end of March, 1919.

To make things clear, I’ll specify exactly what changes from our actual history to make it not happen.

World events in Europe, World War I and its various fronts, North America including the USA and Mexico, and every place else run almost precisely as they did in real history up through 1916, including Wilson’s reelection in November that year.

The slight divergence from our timeline that starts happening in 1916 is an elevated level of petty personal political drama in the military circles around the Kaiser, that turns out to have consequences that are not so petty, but are policy relevant, after all.

They start in the mind of Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Alexander_von_Müller) Chief of the German Imperial Naval Cabinet and personal friend of the Kaiser, and distress he feels over the increased tension in early 1916 that led to the resignation of Alfred Von Tirpitz as State Secretary of the Imperial Naval Office on March 15, 1916. The famous Tirpitz, aligned with the Kaiser for years as a booster of the large fleet, had increasingly been at odds with the Kaiser and Bethman-Hollweg over restrictions on U-Boat rules of engagement in the aftermath of the Lusitania sinking and the American negative reaction to it. Tirpitz agitated against restrictions in the press, and threatened to resign multiple times before doing so, causing the Kaiser stress, and thus causing Muller stress.

In this timeline, his protectiveness of the Kaiser, and his anger at Tirpitz prima donna self-aggrandizing style, angers Muller a great deal and makes him warier of prima donna Admirals and Generals trying to push around the Kaiser.

Admiral like OTL takes care of personal naval/military management and briefing of the Kaiser, along with his Army counterpart Generaloberst Moriz Von Lyncker, and they see it as their duty to keep the Kaiser’s spirits up, keep him engaged in affairs of state and public appearances, but well-advised in his and the state’s best interest, which both Muller and Von Lyncker see as the same thing.’’

But the Tirpitz drama turns both men off to out-of-control, prima donna flag officers, and encourages them, especially Muller, to cultivate their own information and support networks in their services.

In Muller’s case, this means over 1916 learning more about the U-Boat service and its operations. U-Boat production. Tactics. Talks with skippers. One of the first things he learns by spring or summer 1916 is how, despite how enthusiastic Tirpitz was unrestricted submarine warfare by 1915 and 1916, he did very little pre-war, or even up until the day he resigned, to build very many of them for a mass unrestricted campaign, compared to other ship types. This increases Muller’s distaste for the man.

Over the rest of the year he learns other things, from engagements with U-Boat Captains/skippers. The difference between following Cruiser rules and unrestricted rules actually is not that urgent to them, and most of the time, for the armament they have cruiser tactics are what they naturally use, because they are better armed and can more effectively see what they are doing against targets when they surface and use their guns rather than their sparse number of torpedoes. It’s also good for crew exercise and morale when they get to surface and storm aboard a captured prize. This is contrary to Muller’s expectation, when it turns out that it is more the Admirals, not Captains and crew, who chafe at the ROE restrictions.

This further adds to Muller’s skepticism of the unrestricted submarine chorus, now being championed by Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, head of the Imperial Admiralty Staff, and the popular Generals of OberOst, Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

Muller makes contact with naval intelligence people, who on the one hand are supporting “analysis” naval figures like Holtzendorff are using to purport that unrestricted ROE would be a huge factor in crippling British tonnage for vital imports, but also obtains reports and data on German interned merchant tonnage in US ports, US fleet strength including in destroyers, and the role of US and other third party and western hemisphere ports in any successful blockade breaking Germany is accomplishing. Much or all of this material being left on the cutting room floor when being ultimately prepared for and presented by Holtzendorff.

Ultimately, Muller’s efforts, pre-briefing of the Kaiser at opportune moments and making allies in the navy and sowing doubts alters the bureaucratic battle within the German fleet and military that led to the presentation of unrestricted submarine warfare as a “miracle cure” for Germany’s desperate war effort by the end of 1916.

9 January 1917 German Crown Council meeting - Wikipedia

While it would be dramatically fun to have Muller present a counter-memo to Holtzendorff debunking his memo, Pless conference - Wikipedia

Muller probably would have had to do groundwork beforehand to undermine it, pointing to its blindspots or errors which included:

- Underestimating the amount of *immediate* assistance the US Navy and customs authorities could start providing to the Entente blockade

- Underestimating the amount of interned German and Austrian shipping the Americans and Entente could almost *immediately* put into service supplying the Entente, undoing at least a few months worth of U-Boat campaigning in terms of tonnage sunk

- Underestimating the amount new escort vessels, including destroyers, that would become available from the US Navy from nearly the beginning of hostilities that would negate some positive effects of U-Boat campaigns.

- Over-estimating the additional marginal tonnage sunk and cargo voyages prevented by indiscriminately targeting all shipping including neutrals

- Underestimating the decent progress of the current campaign

- Underestimated the number of boats needed to achieve the cargo losses promised per Holtzendorff.

…but they don’t rule it out either.

In a compromise, they keep up the current “sharpened” U-Boat campaign against Allied merchant vessels, virtually all armed at this point. They also commit to shift naval construction allocations to enhance numbers of submarines and their torpedo capabilities of submarine for unwarned sinkings for that option and under waterline damage.

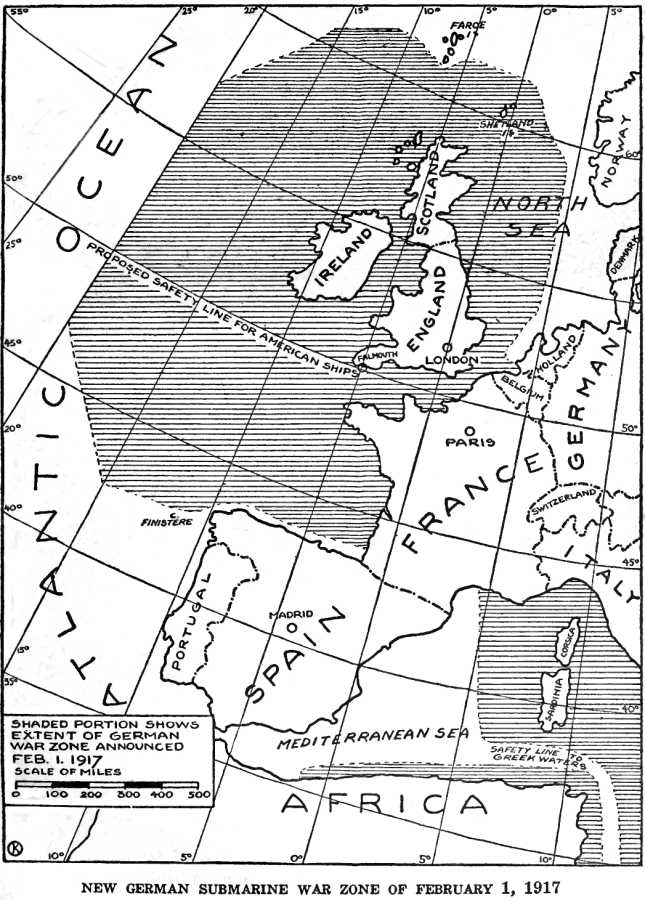

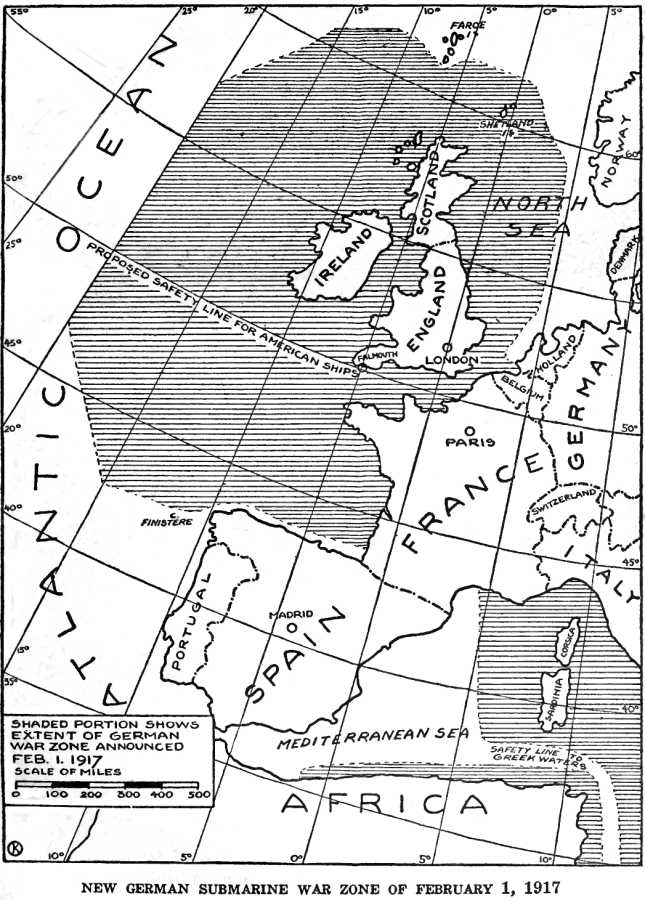

With a greater focus in mind on the naval, and not just military, implications of the USA entering the war against Germany in reaction to an unrestricted U-Boat campaign, the idea that in our timeline led to the Zimmerman Telegram, an offer of alliance to Mexico, and then through Mexico, to Japan, is pursued. But, the whole matter is handled with greater care and security. No messages are sent to Zimmerman over wireless or the wires, even encrypted. Instead, only encrypted *written* instructions delivered in another voyage of the cargo submarine Deutschland, set for January-February 1917 to America and to be courier conveyed to Carranza, with the overture to Japan discussed in Mexico City, in their embassy if possible.

The intention is to line up the contingent alliances with Mexico and Japan *before* authorizing unrestricted submarine warfare, and not authorizing it beforehand. And the hardcopy/in-person delivery method makes sure Britain’s Room 40 never sees any of the discussion, which almost certainly dead-ends without conclusion. From Muller and like-minded people’s point of view, Japan with its Navy is the more important of the two, to offset a possible entry of the US Navy, However, Japan switching sides is ultimately even more outlandish than Mexican-American war. Without signals intercepts, the British and Americans hear nothing of the German overtures to Mexico or Japan, except the vaguest rumors, or whatever those two countries choose to share. The Mexicans would say nothing and keep mum I’d say. And while the Japan would report an offer, at the same time, playing loyal while highlighting their value and options, it might not just be regarded in British circles as Japanese self-aggrandizement for diplomatic leverage.

OK – so Germany is going into January, February, March, 1917 operating its ground and naval forces consistently. No new crisis with the USA, and bam! we have the February Revolution in Russia overthrowing the Tsar.

In April 1917 we have the Nivelle Offensive and then mutinies by French troops.

I will go ahead and make another interpretive leap. The Entente will figure out how to survive 1917 financially and economically.

There are some thoughts they could not, and they were running out of backing collateral in North America for loans. And indeed, the Wilson Administration was advising lenders not to make unsecured loans to overseas borrowers.

Certainly, without declaring war, which is not happening, the US government is not guaranteeing Entente loans or granting unlimited credit. Nor can present a “Liberty Loan” as a patriotic duty or sell war bonds for US defense or Entente purposes. And there were internal British memos about running out of financial liquidity at some point in spring 1917.

However, these British memos were likely based on maintaining certain fiscal and trade orthodoxies and assumed non-imposition of different types of austerity and rationing that Britain’s coalition government would have been willing to do rather than lose the war, even if the measures would have been anathema to an Asquithian Liberal government following its 1914 and beforehand principles.

Additionally, while American creditors could in theory start calling British and other Entente loans short, and strictly to account, and then seizing British-owned collateral for non-payment, causing a run on that, resulting in its liquidation and a drying up of credit, that may not be the most likely thing to happen. Banking and industrial concerns were not as strictly separated then, and big lenders would know abruptly pulling credit, rather than extending and stretching out repayment terms, could kill export markets expected for the quarters ahead instantly. So some concerns with cross-ownership across different sectors may literally continue to bank on British and Entente victory, having sunk so much business and investment in them already, convinced they will win, and counting on them as product markets in the near-term.

In any case, the British do still have their shipping resources, untapped, as-yet-untaxed resources and even if running into difficulty getting credit for purchases in the US, can still make vast food and raw material purchases and some light manufacturing purchases from their Dominions and to some extent Latin America.

Now British and Allied shipping should still face a hard time from the German U-Boat campaign, even as it remains under restrictions. It should get worse from them through June-July-August, even if never as bad as it got in real history. And I would expect the British would start convoying by the time they need to, when they calculate that is the more efficient and sustainable overall alternative.

In any case, in real history, and in this timeline, Germany and Austria and the Ottomans were *utterly unable* to go over onto the offensive on *land* against the western powers at any point between August 1916 and March 1918 (a whole 20 months!) or against Italy between August 1916 and October 1917 (14 months) and I don’t see what would make that change here. From August-December 1916, all the Central Powers could accomplish on land in Europe was holding off the Brusilov offensive, mounting a counterattack to it, and counterattacking the Romanians and squeezing them out of Wallachia and Bucharest. Any other successes by the Bulgarians and Ottomans were defensive stalling, and in Anatolia/Caucus, the Turks were failing at that.

In 1917, the Central Powers, despite the rot and end of discipline and motivation in the Central Powers and the mutinies against senseless offensives in France, were unable to mount any land offensives from January through August of the that year. And they had to fend of persistent British assaults in Flanders from May or June through November, the brief French Nivelle offensive in April, some Italian offensives in the summer, a feeble sally from Salonika that year, a successful British advance in Mesopotamia, and British gains in southern Palestine and Jerusalem by the end of the year along with Arab Revolt actions.

And this was all in our timeline before US troops were really in the trenches in any quantity. So the absence of US forces from the war and the trenches through August 1917 does not look at all like it provides Germany or the Central Powers a war-winning opportunity in that time.

What Germany was able to do in 1917 was mount a defense and counter-attack that manhandled Russia’s June Kerensky offensive, and sent Russian morale further plummeting.

Then, in September, taking advantage on ongoing rot/melt of Russian forces, the Germans took Riga.

Then in October-November, the Germans and Austrians together battered the Italians at Caporetto and threw them out of much of Venezia back to the Piave.

Without America in the war, there’s not an apparent opportunity for the Germans to advance to an enemy capital in 1917 to claim a victory, but things can’t be better for the Allies either. The Allies’ offensives are failing.

It is a legitimate question if the Russian Provisional Government even *attempts* an offensive. In our timeline, the Provisional Government was being prodded forward and pep-talked into not only keeping in the fight, but attacking by the mission of American Elihu-Root, who made clear that American financial largesse was on offer for Russia *if* it fought for victory, but “no fight, no loan”. Without the Yankee carrot, the British and French alone might not have enough to offer the Russians to motivate a real offensive from them, even if the Russians would not yet be ready to make a separate peace. Indeed, if Wilson is still on the outside, not wanting a German victory, but not wanting *anybody’s* victory, and supporting a negotiated peace, Wilson might be finding the Russian democratic socialist parties, with their presence in the Petrograd Soviet and in some Provisional Government posts, with their talk of” no annexations and no indemnities” among the most receptive among any politicians in any belligerent state.

*Without* the US having declared war on the Central Powers, and that being noted as a growing danger for them, it is an open question whether or not the Center and Social Democratic parties in the Reichstag voice support for a negotiated peace in July 1917 as they did in our timeline. It is also an open question whether Pope Benedict is moved to offer is August 1917 mediation proposal, which some have interpreted as motivated by the danger to the Catholic Habsburg monarchy by this point in time.

I imagine Britain’s blockade would continue to tighten around Germany, although be little less airtight, a little more leaky, with the USA not a belligerent. It would still get harsher.

But unless things change to somehow produce a negotiated end to the war by November 1917 – not absolutely impossible, but still requiring a near-miracle, and highly unlikely, we would likely have a Bolshevik Soviet revolution pulling Russia out of the war by this point in time.

That would probably ease pressure in Germany for unrestricted submarine warfare, though it still wouldn’t be ruled out, and even though the blockade would be stinging.

The persistent effects of blockade, even without American participation in the war and prospect of ever-growing numbers of American troops, probably would *still motivate* Germany to invest in a spring 1918 do-or-die offensive in the west.

This would have to follow a punishment expedition in the east to stop dilly-dallying and get the Bolsheviks to sign the Brest-Litovsk peace.

By March 1918, we do have some questions about how the Allies have postured themselves defensively, not having American troops in France or on the way.

Have the French raised significantly greater numbers of colonial troops from North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indochina, trained them, armed them, and put threm in the battle-lines in France or at least in the fields and factories of France in numbers far exceeding our timeline?

Have the British sent significantly more of their own men, Dominion men, and possibly men from non-white colonies like India, the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa to fronts in the Middle East, Salonika, and France?

Is that helping keep manpower in terms of battalions comparable to our timeline or not?

If not, why not?

Have the British or French in any manner found something sufficient to bribe Japan with to send a Japanese Expeditionary Force (JEF) to Europe to fight with them? Has it even been discussed? Has Japan mentioned a price? Did the Allies turn away horrified at the price or think about it? –Ultimately, I think any such bargain is really unlikely.

Given the technology of the time, and the tactics, I don’t think a decisive breakthrough and exploitation of Allied lines, gaining either the Channel ports, or Paris, is likely in 1918, and failure to meet these objectives will be devastating to German morale.

However, there is an important question remaining.

Would the British and French need to pull back and abandon peripheral fronts, or starve them, to survive the 1918 German offensive?

For example, pull out of Salonika, dismount the troops in Marseilles or the Channel ports, and head to the lines. Pull back any troops sent to Italy after Caporetto. Strip the forces in the Mideast fronts, Palestine and Mesopotamia, to the bare minimum, and get them back to France?

[Also, would none of the British, French, nor Italians have any troops to spare to intervene in Russia to guard supplies or help the White Russians? I would not see the Americans involved in Russia, even in Siberia, if they are not already in WWI. This leaves only the Japanese to possibly involve themselves.]

If the Allies have to do this to survive, they stop the Germans, but they are too exhausted to immediately launch non-stop counter-attacks beating the Germans back. The Allies have to cut off the most threatening forward positions, build up colonial reinforcements and supplies, build up gas and tanks and aircraft, keep up the blockade, and be ready to have a go in 1919.

And thanks to withdrawals in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Italy, the Central Powers of the Ottomans, Bulgarians, and Austro-Hungarians will be under less pressure along with Germany and they’ll all make it through another nasty winter and New Year.

However – If on the other hand, the Allies are able to halt the Germans in the west through external/colonial/home reinforcements, German logistical over-reach, while *not* stripping down the other fronts, it is a different story.

The Allies without the Americans would probably have too thin a manpower buffer to prosecute the OTL 100 days offensive of hammer blows in the west. But the men in the west who survived the German onslaught and building up for 1919 will be cheered a bit by good battle news in the fall in September from the Middle East, and then the Balkans from Vardar Macedonia, as in October and November the Bulgarians, then Ottomans, and then Austro-Hungarians collapse.

To the surprise of almost all, the decisive campaigns entering German soil over the winter months of 1918-1919, and compelling German surrender and setting off German revolution are not on the western front, they are rather the efforts led by Armando Diaz crossing Austrian Tyrol, Austria proper, Vienna, and Salzburg, to advance to Munich, and parallel advances by Franchet D’Esperey’s L’Armee D’Orient of Frenchmen, Serbs, and Greeks, riding the Austro-Hungarian rails, soon joined by Czech and Polish volunteers, collecting in Prague, advancing into Saxony and Silesia, and then on to Berlin and Brandenburg from the south. The role of the hard-worked western front armies is to keep contact with and pressure on the German western front forces and collect increasing numbers of PoWs.

In Germany’s increasingly desperate situation, there are attempts to shift forces to close the wide open breach in the south and east at the tail end of the war, by transferring troops and units from the western front via the rails to Bavaria, Saxony, Brandenburg. However, success is limited. Because of the late start, Allied forces are reported breaching the Reich borders at Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, before much in the way of any transfers have been completed. Some local commanders who haven’t lost faith resist redeployments, not wanting their sectors in the west to break. Other units embarked on the rails and roads, “get lost” on their way to the other fronts as soldiers desert and wander home to check on family rather than stay in order or mass on the other border. Some troops resort to minor self-wounding, self-maiming to avoid further duty. Others in more exposed positions, especially as bad news from the southeast spreads, surrender to the nearest Allied forces to get rations and a dry cot.

These forces all add up to total disintegration of the German position before the winter is over, possibly before the end of February, definitely before the end of March, 1919.